By Hazel Appaqaq | 10 minute read

Sitting crammed together at the last coffeehouse, a snippet of whispered exchange between a pair of boys, inexplicably dressed up in costumes —a firefighter and a policeman— the one trying to point out to the other an adult in the room, went:

“…That one, the one with the grey hair,” said the firefighter.

To which the policeman hissed, “Which one with grey hair?”

In step with the population curve of the previous millenium, our tiny community’s abundance of grey and silver haired residents is plain. As the events of our time reverberate through our midst, what seems more salient is the island’s unusual preponderance of youthful elders, wise young people, and people of all ages tuned into their own simple, radical frequencies. While the common definition of what can be expected is unsettlingly lax, this richness of perspective and experience is one resource among many that we can tap into to support our growth through current trials. In situations that push us past our thresholds of acceptable hazard, further into the unknown than where we’re accustomed to dwelling, what do we normally rely on to suss out appropriate action? Or, more specifically – who? In a poetic interpretation of the mundane, there’s a double meaning in looking to the ‘WHO’ for intelligence and direction. Because who else do we ultimately fall back on in circumstances of extreme ambiguity, but the inner sage or crone, the wise grandparent whom we carry inside at all times? It’s hard to allow this one the space to come forward and speak, when a constant stream of information, commentary and an atmosphere of anxiety is at every moment, corralling our energy into an outwardly assessing, defensive posture. Yet the scenario playing out today on the world stage is an example of when the strength of our connection to that invisible advisor is most needed. Likewise, when trying times strike our individual lives in the form of misfortune or painful passages, they paradoxically bring light to that critical bond with the inner guide, otherwise known as the guru, by threatening it. A potentially fateful development in the public narrative is an increased awareness of the eldership and the physically compromised: the diseased, the infirm, the holders of knowledge and memory. Alongside developing pragmatic plans for our long-term adaptation, could this parallel a signal from the unconscious to acknowledge, honour and nurture their equivalents within each of our beings? Such a goal, undertaken at the level of human society, would comprise a kind of industry and development other than those that we’ve been enacting in recent ages, in pursuit of a similarly other kind of exploration and expansion. Perhaps we’re being called, as a global community, to embark on the ancient quest with an inward direction. In our Northern Gulf neighbourhood of open-minded eccentrics, we’re propitiously poised to contribute to such a mission. With so many diverse expressions of seasoned knowledge, from alternative counsellors, healers, artists of all makes, and farmers, to inspiring examples of families simply carving out a life here, the challenge of meeting with life’s difficult transitions could be viewed as a profoundly intricate, multifaceted puzzle that begs to be solved.

Accordingly, in an attempt to draw a few pieces closer together (and since these are produce articles), my next few posts will be a series focused on local food and land based perspectives on the much talked-about, current transpirations in this, our shared story.

Sara Stewart is a new farmer to the island, most directly from Powell River, who transplanted herself here to eke a living out of the sandy acres at Reef Point Farm. In a recent conversation with her, she described the balance that she strikes in the farmer’s life of numerous extremes. On a basic, fiscal level, there’s the frustrating fact that for small farmers, especially ones starting from scratch, the game is, by all appearances, rigged to bamboozle them out of every last dime in their pocket. Absolutely everything one might need in the way of tools and materials costs an arm and a leg. Part of the problem is that society keeps coming up with annoyingly specialized farming tools that do one thing, and one thing only. Want to reduce your water consumption because you live on an island where the summertime water table is overdrawn? No worries, you can get drip line for that! That’ll be a thousand dollars, please. Oh, and if you want to fix it when it springs a leak, it helps to have drip line-specific maintenance tools. Interested in no-till methods of loosening the soil? Lucky for you, there’s a drill-powered, walk-behind tilther for that, for only another thousand! Or alternatively, you could just buy your own rototiller and get a tilther attachment for ten grand. And on and on and on… The specialization of farming equipment benefits the large-scale agricultural model, but for the little people, it represents a selective standard of nerve wracking, financial risk. All of this is not to mention the continually climbing cost of seed, the expense of compost, reemay and plastic mulch, hand tools, potting mixes, minerals, harvesting containers, packaging materials, a delivery vehicle, and of course the biggest expense of all – the restrictive price tag on arable land. This is why, as she pointed out, most successful farmers function with a spouse or business partner, because shouldering these costs alone, and the stress behind needing to pay them off, is twice as hard. Yet, that is precisely what she’s doing this season! After the purchase of all the necessary startup inputs, together with the lease agreement for the land, she confided to me the percentage of her budget that she’s reached – and the number is high. It’s a teetering high stakes game, and she’s all in. One of her strategies for dealing with the imperative for making back her investment (and a living of course), is to do as much prep work now, in the shoulder season, while things are still moving slowly. Then, when the pace of growth speeds up, and the workweek becomes a race to keep up with the planting and harvesting schedule, there will theoretically be less things to impede that flow. Theoretically.

On the 27th of March, a virtual meeting was hosted by Noba, aimed at formulating an overview of the island’s needs, and ways in which we can adapt to the new terms of a pandemically affected world. There was a general consensus that on multiple fronts, one key to taking our communal health in hand is linking up all available resources with those in need. In a subgroup focusing on food security, a similar suggestion voiced by Tamara McPhail spoke to the up-front costs of increasing the dimensions of our local food production. The request could be made to Cortes’ wealthier residents to purchase machinery, or donate towards infrastructure or educational programming, in acknowledgement of being beneficiaries of the essential role provided by local growers. Perhaps this vision could give rise to a new process of fruition, but regardless of what we manage to assemble, the farmer’s lot will remain a calling with a high investment load. There’s also the allocation of time, physical energy, and the mental effort of staying organized, in touch with the pace of growth, and sensitive to continuously arising issues. Sara expressed the weight of this last in both inspiring and deflating tones. On one hand she appreciates the permaculture concept that the problem is the solution, and how that motivates her to see all problems in this light, not only on the farm. On the other hand, it’s a harsh, relentless requirement to spend so much time combating and withstanding the elements, and when she can’t make productive headway from the comfort of an office, one that dampens the spark of her curiosity. In this regard she relates that the work can be demoralizing: a highly committed relationship to a monetarily undervalued occupation.

In response to the quandary we’re all in, a rising harmony of Cortesian voices has expressed a deepening gratitude for our food and health systems. Additional to this silver lining, a less articulated viewpoint is the framing of it through a permaculture lense. From this angle, the small farmer’s acclimatization to extreme risk via personal commitment demonstrates a difference in posture that can be adopted towards the conflicting challenges of our times. Take the example of the competing problems described above: an increased participation in local food production can be met by the spirit of stepping up and offering whatever one is available for. This would mean allowing for a different outcome than the economically driven farm business, but imagining instead what a fulfilling use of one’s own skill set could produce in tandem with the contributions of other creative co-conspirators. Once a way of being financially feasible is figured out, the option becomes available to act less for profit, and more for the expansion of a directly lived connection to this land, beyond our appreciation of her beauty. The majority of us have set roots down here for the remedial, alternative existence that this place offers to the numerous, mounting pandemics common in the city, the suburb, and the metropolis. We already harbour the awareness that the structures of society, in particular the economy, seek to make consumers of us all, thereby compelling us toward the fulfillment of its goals. The local grower’s lifestyle exemplifies the inherent power in “just doing it”: the momentum accumulated for paradigm shift by getting up each day and prioritizing one’s true values. Like Sara, many of us are newcomers to this island, relative to the indigenous people that populate its forests and shores. For the past century we’ve enjoyed the privilege of being able to stroll off the ferry and start gardening – how incredible to have such a gift within our reach! A line of questioning that can be formulated by looking at current events from an elevated perspective, as if by watching the goings-on from one of Cortes’ majestic peaks, is: What are we willing to do for our health? What are we willing to do for our ability to eat vibrant, low-impact, high-quality food? What are we willing to do for the benefit of the human and ecological neighbourhoods from which we draw a daily sustenance, a livelihood, a life?

Whether by conscious choice or synchronistic wending, the decision to make an abode here usually flows from the deep sense of repose that becalms us from within nature’s awesome and soothing embrace. You know the feeling – the one that sets in on the second ferry ride, on the way back to Whaletown. At first it’s as gentle as the tide lapping at your feet, and gradually as the distant topographic features coalesce into her rich tones, her jagged edges and fluid curves, as the spacious perspectives eventually encompass you, by then you can feel it in your belly. Home. The feeling of sanctuary is palpable, through the tripled effect of removal from the mainland. This “end of the road” factor can manifest in a mentality of retreat… kind of reminiscent of being in an encampment of hermit crabs. Though it’s true that it can take years for one’s path to cross with that of another scruffy year-rounder, it’s also true that we’re all just down the road from each other, that what affects one is bound to affect us all. The morphing conditions in the realm of public health, themselves possibly echoes of the transformations in the climate’s health, bring this fact into vivid focus, as in one way, we’re being forced into deeper isolation from each other, yet in another, guided out of the normal, familiar confines of the island hermitage. There are many ways in which we need to grow into a new definition of society; and as fortune would have it, there’s a wealth of passions and wisdom among our number regarding the different directions that can take. But at least one vector has the ability to further strengthen the adaptive process. In a reversal of an historically appropriate aphorism, the challenge of needing to feed ourselves can “carry the seed of its own solution.” If by overcoming our species’ flawed thinking of self-preservation through self-interest and separation, could a critical mass of us find the motivation and the commitment to jump on the bandwagon trundling towards co-operative farming? And if this were to happen, could the joy of being in touch with the soil and the environment, and in giving selflessly to each other, turn the problem of the cost of production on its head? Sara’s personal experience of this alchemy is that the pleasure of the art form far outweighs the costs, from how honoured she feels to provide this service to others, to her amazement every single time a seed sends a tendril poking up from the soil. Could the “cost” of growing together end up being a cherished resource that nurtures and nourishes even more than the crops? It doesn’t sound like such a stretch to these ears. In fact, maybe in the ironic ingenuity of the cosmos, this experience is an opportunity, occurring to us all, that we might develop a deeper capacity for compassion and gratitude… since the one thing that gratitude germinates from most potently is its opposite, the pain of loss. So another saying goes, “We don’t know what we have until it’s gone.” But the second part should be: “…But then, like the dawning of a new day, we can know.” The first part on its own paints us as foolish, backward creatures, always on the wrong side of fate. But the deeper, true meaning points to the miraculous, ever-renewing way that we do learn from our foibles and our weaknesses – and how we can manage to turn fate over in our favour.

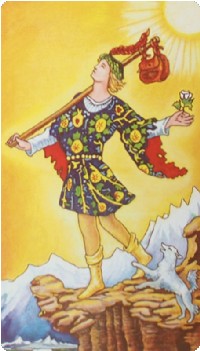

As our earthly home spins into a new month, the month symbolically associated with The Fool, it would be a shame to trudge by the ancient significance of this archetype, too burdened by the load of presently occuring struggles to notice its guidance. Consisting of a tarot card without a denomination, his wisdom pervades the rest of the deck; mirroring how he derives a belonging from everywhere and nowhere.

In the image, the figure blithely steps off the edge of a cliff – a gesture which on the surface epitomizes the normal sense of foolish behaviour – self-destructive, self-defeating, unwise. But looking at his uplifted stance, a Peter Pan-like lightness speaks of his trust in the perfection of the All, his complete acceptance to being in the hands of fate. But where Peter Pan’s distaste for old age carried him into a fantasy realm, the Fool’s path opens to the World, through his integration of the child’s curious, seeking spirit with the elder’s deftness at distilling experience. He carries a very small bundle of belongings, showing that one can only ever be minimally prepared for life’s journey, if at all. The point is not to be prepared, only rather to embody a readiness. This quirky character is a simpleton at heart, with a radical demeanor towards life – much like the average Cortesian! His example can be sublimated to the level of action starting with a simple shift in posture, an upward and outward turning, itself supported by feeling the containment and solidity of the earth below – our oldest ancestor.

Whenever the hand of rapidly changing circumstances effectively pulls the rug out from under our feet, threatening to making fools of us all, this felt sense can be heard from within, whispering:

Why not?

Rebeka Carpenter

Thank you for your thoughtful and moving writing summarizing our shared Cortes moment…may we find our way towards caring for our oldest ancestor!

Max

woah. nice writing. I like the alliteration sprinkles and the invitation to expand my vocabulary.

Tell me more about co-operative farming sometime.